Our Service

Industriarbetsgivarna works with questions concerning being an employer within Swedish industrial companies. We support our members with advisory service in every day matters, legal advise, negotiations with trade unions regarding collective agreements and labour law, expert support, and courses tailored to our industrial companies.

We negotiate on pay and general conditions within our collective agreements for the member companies. Collective agreement negotiations are at heart of Industriarbetsgivarna’s activities.

We also offer ongoing advice on laws and agreements as well as investigations and development work. Further, we help member companies with legal assistance in court proceedings.

Our work is designed to make life easier for our companies, so they can concentrate on their core business.

The companies that form Industriarbetsgivarna have a number of things in common:

- The companies are highly dependent on exports to the world market. Therefore, long-term international competitiveness is an extremely crucial issue.

- The companies are capital-intensive, with facilities which demand major investments with long planning horizons, and so they need long contract periods.

- The companies have a major need for skilled employees. The whole world makes stringent demands of the companies’ adaptability and so has strict requirements in terms of flexibility and expertise.

- The companies base their operations on raw materials. Easy access and the price of raw materials are fundamental to their business.

Employers’ Information

Below you will find employers’ information about the Swedish labour market, what a collective bargaining agreement is, the Employment Protection Act, Co-determination at the workplace, work environment, and discrimination and equal opportunities in the working life.

Among the reasons for this cooperation was a shared wish to avoid government intervention, which the parties felt could easily result in depriving them of their freedom of action. In this spirit, a number of joint or collaboration agreements were signed, which exercised a considerable influence over both companies and employees.

The model, however, did not unaffected survive the 1970s` ideological stalemates and years of economic difficulties. In this decade, the majority of the labour laws that today regulate the labour market were made and this explosion of labour laws changed the tradition of regulating these matters between the parties. The new legislation was to a large extent introduced at the express wish of the influential major union organisations. However, since the collective agreement by tradition has had a larger impact than individual regulations, many of the issues that in other countries are regulated by law are in Sweden still stipulated through the collective agreement. For example there are no laws on minimum wage.

Sweden became closely associated with the European Union (then the European Communities) in 1994 through the EEA agreement and became a full member of the union on 1 January 1995. The membership has influenced the Swedish labour market through the introduction into Swedish legislation of the labour related legislation of the union. This has had effects inter alia on the Swedish legislation pertaining to discrimination, equal opportunities and pay for men and women and the effects of a transfer of a business etc. It has also opened the Swedish labour market to employees from the other member states.

Typical for the Swedish labour market today is in short the following:

- 68% of the blue collar and 73% of the white collar labour force is a member of a union (2012) according to The Swedish Trade Union Confederation. The employers are very well organized too. This is a necessary condition for the option to regulate through collective agreements.

- The labour market is relatively homogenous.

- The right to negotiate is very wide and stipulated through law.

- Unions with a collective agreement are privileged.

- The right to industrial conflict is very wide and strongly centralized. The individual cannot decide to go on strike. That decision rests with the organizations.

- The regulations are about the same for both the public and the private sector.

- There are very few special regulations for smaller companies.

What is a Collective Bargaining Agreement?

Collective bargaining agreements are very common on the Swedish labour market and to a very large extent regulate the relationship between an employer and its employees.

Some collective bargaining agreements pertain to the general relationship between an employer or and employer federation and the trade unions. Such agreements normally regulate such matters as co-determination, procedures for negotiations and the outlining of common objectives relating to the future development on the labour market and for the employers. Agreements with the above subject matters are normally entered into between the nation-wide employer’s federations and their nation-wide central trade union counterparts.

Other collective bargaining agreements provide rules governing the relationship between an employer and individual employees. Agreements of this type can be entered into both on a central level, by the parties described above, and on a local level between a specific employer and the local trade union present at the company. It is common that a central agreement pertaining to the individual employee’s terms and conditions of employment are complemented by local agreements. This is the standard procedure among the companies being members of The Swedish Association of Industrial Employers.

The Swedish Association of Industrial Employers is bound by thirteen collective bargaining agreements. Seven of them are blue-collar agreements. The blue-collar trade union Industrifacket Metall is counterparty in five agreements, Pappers (The Swedish Paper Workers Union), GS (The Swedish union of forestry, wood and graphical workers) in one each and SEKO (The Union for Service and Communications Employees) in two. The Swedish Association of Industrial Employers is also bound by four collective bargaining agreement for white collar employees. The counterparties to this agreement are the white-collar unions Ledarna (Sweden’s Organization for Managers), Unionen and Sveriges Ingenjörer (The Swedish Association of Graduate Engineers) . In addition, The Swedish Association of Industrial Employers is bound by one collective agreement that comprise both blue- and white collar counterparties in the same agreement with Pappers (The Swedish Paper Workers Union) as blue-collar counterpart.

All above mentioned agreements regulate such matters as terms and termination of employment agreements, working time, minimum wages, vacation compensation and sickness compensation etc. As mentioned above, these agreements are often supplemented by local collective bargaining agreements.

The definition of a collective bargaining agreement can be found in the Co-determination Act, which states that a collective bargaining agreement is an agreement in writing between employer’s organisations or an employer on the one hand and an employee’s organisation on the other hand, which regulates conditions of employment or the relationship between employers and employees. An agreement is deemed to be in writing if its contents has been recorded in approved minutes or where a proposal for an agreement and an acceptance thereof have been recorded in separate documents. Oral agreements, or agreements which do not concern the relationship between employers and employees are not deemed a collective bargaining agreement.

The two most important consequences of a collective bargaining agreement are:

– that departures in individual agreements from the terms of a collective bargaining agreement are invalid if both parties to the individual agreements are bound by the collective bargaining agreement and the departure is not expressly permitted by the collective bargaining agreement (This is called the “mandatory effect of collective bargaining agreements”).

– as a rule, it is not permitted to resort to industrial actions (e.g. strikes and lock-outs) during the term of an agreement with the objective of altering the agreement or exerting pressure in the event of a dispute over the implications of a collective bargaining agreement (this is called the “peace obligation”).

Collective bargaining agreements are signed for given periods, normally between two and four years. A collective bargaining agreement is binding both on the employer’s organisation and its members on the one hand and on the union and its members on the other hand. Furthermore, as a general rule, a collective bargaining agreement is also in practise, if not in theory, binding on non-unionised individual employees and unionised employees who belong to other unions than the union being part to the agreement, provided that (i) the employee works with tasks that are covered by the agreement and (ii) the union that the employee belongs to is not itself bound by another collective bargaining agreement with the employer.

A collective bargaining agreement is reached by means of negotiation. The Co-determination Act makes it clear that each union organisation and employer or employer organisation shall have the right to negotiate in all areas which affect the relation between employer and employee. This may be a question of regulating by means of an agreement issues remaining unresolved between the parties or of replacing previously existing regulations by new ones. A right to negotiate for one party means an obligation for the other part to participate in the negotiations. However, there is no legal obligation to come to an agreement (For further information, see under the section “Co-determination at the workplace”).

It is without doubt the single most important legislative act regarding employee influence at the workplace. The act is discretionary legislation which enables the parties on the labour market to come to more detailed agreements on participation by the employees by means of collective bargaining agreements. In addition to defining the prerequisites of a collective bargaining agreement (see under the section “What is a Collective Bargaining Agreement”), the act contains regulations governing the following main issues:

The Right of Association

The employee and the employer have a right to join associations and engage in activities through these without hindrance by the other side. This is referred to as the right of association. This right has been regulated by statute for many years and is the major legal ground upon which joint action by unions may be based. The Co-determination Act provides that the right of association shall not be violated. If an employer takes action against an employee on account of his/her trade union membership, or activity on behalf of the trade union, the employer may have to pay damages. Critical or adverse comments are not normally in themselves regarded as a breach of the right of association.

The Extended Right of Negotiation

According to the Co-determination in the Workplace Act, an employer is obliged to initiate and carry out negotiations with a trade union that has a collective bargaining agreement before making and implementing a decision concerning major changes at the workplace in general or for individual employees. This is referred to as the primary obligation to negotiate. Should the employee’s side so request, the issue may be referred to negotiations at central level. The employer must defer the decision and the implementation thereof during the entire negotiations procedure.

In all other questions, a union bound by a collective bargaining agreement has the unilateral right to demand local and central negotiations. In such cases, the employer is also obliged to delay making the decision or to postpone implementation of a decision which already has been made.

The extended right of negotiation does not imply any legal obligation on part of the employer actually to reach an agreement. If the negotiations come to a conclusion without an agreement being reached, the employer is entitled to make his decision in whatever way he finds appropriate. The employer is also entitled to make decisions unilaterally once the negotiations have been completed. In some extreme situations the employer is entitled to make a decision and implement it before negotiations have been carried out. This exception occurs only very rarely.

The Extended Right to Information

The information rules in the Co-determination Act in principle imply that there should be an open attitude towards giving the employees insight into the progress and circumstances of the company in various respects. In the first place, the employer is obliged regularly to inform his local negotiation counterparts about the development of the business in financial and operational terms and about personnel policy guidelines. This obligation is called the primary obligation to inform.

The union is also entitled, upon request, to examine accounting records and other documents to which the employer has access and which, as an organisation, it needs in order to safeguard the common interests of its members. Copies of documents etc. need only be provided if this does not lead to unreasonable costs or difficulties. In certain exceptional cases, the employer is released from the obligation to inform.

The extent of the trade union representatives’ duties to keep the information that they have received confidential is primarily determined through negotiations between the parties. If no agreement can be reached, the employer must apply to a court for a decision concerning secrecy. Such a decision is only made if there would otherwise be a risk of serious harm being done to employers affairs. It should however be pointed out that trade union representatives are also always covered by either explicit or implicit clauses in their employment contracts which prohibits disclosure of confidential unformation.

The Interpretive Precedence etc.

In addition to the provisions regarding negotiations and information, the act also contains provisions that give the view of the trade union precedence before the view of the employer in certain disputes. The interpretive precedence is applicable until a court has decided on the matter. The issues where the trade union has this so-called interpretive precedence concern cases of disputes regarding the extent of an individual employee’s duty to work, disputes concerning wages or other financial remuneration and disputes regarding so-called co-determination agreements.

Furthermore, the act provides that an employer is obliged to enter into primary negotiations before deciding to engage a subcontractor, viz. to engage persons who will actually not be employed by the said employer. The counterparty to the negotiations is the union which the employer has a collective bargaining agreement with covering the work that the subcontractors shall carry out. There are only a few situations where the employer does not have to negotiate. The act provides that the central unions under certain circumstances have a right to veto the employer’s decision, thus preventing the employer from engaging a sub-contractor. This can only be the case if the sub-contractor can be shown to be disregarding laws or collective bargaining agreements or is acting in some other way in serious conflict with general practice in the relevant industry. The right of veto has a relatively restricted purpose and may therefore not be used to ensure that certain work is reserved for the employees at the company in question.

The act is applicable to all employees, both in the public and private sector. However, a few groups of employees are excluded from its application. These groups are:

- (i) employees who, by virtue of their duties and conditions of employment, may be deemed to be in a managerial or comparable position,

- (ii) employees who are members of the employer’s family,

- (iii) employees who work in the employer’s household and

- (iv) employees who are employed for work with special employment support or in sheltered employment.

The Employment Protection Act contains fundamental rules applicable to the individual employment agreement. Thus, it contains provisions pertaining to the commencement of an employment, and the termination of an employment agreement. The principal rule of the act is that employees shall be employed for an indefinite period of time. Consequently, the act restricts the right for an employer to employ a person for a limited period of time.

The act contains extensive provisions for damages in the event of an employer contravening the act.

The rules Pertaining to Termination of Employment

According to the provisions of the act, an employer who wants to terminate the employment of an employee must be able to show objectively justifiable reasons for the termination. If an employer performs a termination without such reasons being at hand, the employer may have to face both claims for an annulment of the termination and claims for damages. The damages may in some situations amount to as much as approximately two to three years’ salary for the employee.

The objectively justifiable reasons that an employer must show are divided into two categories. The first category consists of terminations based on reasons related to the employer. Such terminations are called terminations due to redundancy. The other category consists of terminations where the reasons for the termination relate to the affected employee in person. Such terminations are called terminations due to personal reasons. The procedures for the two categories of terminations are similar in some respects, but there are also very important differences. Thus, they will be described further below under separate headings. Furthermore, the act also provides for a possibility for an employer to dismiss an employee without any notice period in case of a serious breach of the employment agreement by the employee. Summary dismissals are also described further under a separate heading below.

Terminations Due to redundancy

One of the fundamental principles under Swedish labour law is the employer’s freedom to organise and run the business any way that the employer deems fit, subject to the obligations to negotiate and inform the trade unions, as described under the above heading Co-determination at the Workplace. Thus, the employer is at any time free to re-organise its business, e.g. in case of poor profitability or due to a wish to rationalise etc. Such a re-organisation may cause a need to reduce the headcount.

The first step in a re-organisation procedure is to negotiate about the re-organisation with the trade unions. The negotiation concerns the decision to re-organise. The employer may not take the decision before the negotiations, since this would deprive the union of its possibility to influence the decision. Once this negotiation has been concluded, the employer can take the decision to re-organise the business. If the re-organisation entails a reduction of the headcount, the next step is to negotiate regarding which employees shall be laid off. Only after this negotiation has been concluded can the employer notify the affected employees of termination.

The fundamental principle applicable when deciding which employees shall be made redundant is the so-called last in-first out principle. According to this principle, the employee with the longest aggregate period of employment is entitled to remain employed the longest, provided that he/she has sufficient qualifications for any of the remaining positions. If two employees have the same period of employment, the oldest employee takes precedence. Thus, one of the first steps in a redundancy procedure is to create a list over the employees based on this principle.

The next step is to identify which positions will be made redundant. Since the above principle is decisive when determining which employees shall be made redundant, it is possible that it is not the employee who is holding the redundant position that will be given notice. Instead, the employer must investigate whether there are any vacant positions that the affected employee can reasonably be relocated to. A prerequisite for such relocation is that the employee has sufficient qualifications for the alternative position. If there are no such positions, the employer must investigate whether there are any positions held by employees with a shorter period of employment that the employee can be relocated to. Again, the employee must have sufficient qualifications for the position in question. Only if it is not possible to re-locate the employee as described above does the employer have objectively justifiable reasons for a termination.

All collective bargaining agreements that the Swedish Association of Industrial Employers are party to contain provisions that make is possible to deviate from the priority rules described above. However, any deviations require an agreement with the trade union in order to be enforceable. The provisions of the collective bargaining agreements make it possible to agree with the unions on a so-called “agreed priority list”. If such a list is agreed upon, it is possible to select the employees to be given notice using other criteria than period of employment and qualifications, criteria which are more relevant to the employer.

Once the employees to be given notice have been identified and the union negotiations have been concluded, the employer can go ahead and serve notice of termination. The notice period normally ranges between one and six months, but may in some situations be as much as 12 months. The employee is entitled to all his/her benefits during the notice period. The employer can request that the employee works during the notice period, but may also relieve the employee from his/her duty to work.

Employees who have been employed for at least twelve months during the last three years have a priority right to be re-employed by the employer, in case the employer needs to recruit new employees. This right is vested with the employee from the time when notice of termination is given until nine months have elapsed from the end of the employee’s employment.

Terminations Based on Personal Reasons

It is normally difficult to terminate an employment due to personal reasons. Furthermore, as in redundancy situations, the employer must try to relocate the employee to any vacant positions before the employment is terminated, provided that this is reasonable and the employee has sufficient qualifications for the position.

Termination for personal reasons may be possible if the employee has committed a serious breach of his/her employment agreement, such as in cases of crimes committed against the employer or against colleagues, or in serious cases of disloyal behaviour. Extensive and unauthorised absenteeism may sometimes also constitute an objectively justifiable reason for a termination, as may grave cases of poor performance. On the other hand, an employee’s illness very seldom constitutes grounds for a termination.

Before an employer can terminate an employee due to personal reasons, the employer must normally have made the employee aware of the unacceptable behaviour that the employee is guilty of and tried to correct it. Furthermore, the employee must have been given a reasonable chance to correct his/her behavior.

The first step in a termination process is that the employer informs the employee that the employer intends to terminate the employment. This information shall be given at least two weeks before the notice of termination is given. The employee’s union shall simultaneously be notified. The union and the employee are entitled to consultations with the employer regarding the pending termination. If such consultations are requested, the employer must postpone the termination until the consultations have been concluded. During these consultations, the parties normally discuss whether or not objectively justifiable reasons for a termination are at hand.

Summary Dismissals

An employer may in some situations summary dismiss an employee. This is possible if the employee has committed a very serious breach of the employment agreement. Examples of such serious breaches that may constitute cause for a summary dismissal are crimes committed against the employer, such as theft or assault of a colleague.

The procedure for a summary dismissal is similar to the process for a termination due to personal reasons. However, there is no obligation for the employer to try to re-locate the employee. Furthermore, since a summary dismissal may only be carried out in case of very serious breaches of the employment agreement, the employer is not under any obligation to try to correct the employee’s behaviour and give a “second chance”.

As in case of a termination due to personal reasons, the first step in a termination process is that the employer informs the employee that the employer intends to terminate him/her and notifies the union. This information shall be given at least one week before the summary dismissal is executed. The right of the employee and union to have consultations and the obligation for the employer to postpone the execution of the summary dismissal are the same as in case of a termination due to personal reasons.

Remedies in Case of Unlawful Terminations

The remedies available to an employee who believes that the termination of his/her employment was not based on objectively justifiable reasons is to request that the termination shall be declared invalid and to demand damages. The damages available under the Employment Protection Act are divided into two different categories. First, the employee may demand damages for the offence that the employer has committed by the unlawful termination. Second, the employee may demand damages for economic loss. The damages for economic loss are capped and are maximized to 16 monthly salaries if the employee has been employed for less than five years, 24 monthly salaries if he/she has been employed for five years or more but less than ten years and 32 monthly salaries if the employee has been employed for more than 10 years.

If the employee requests that the termination shall be declared invalid, and this issue cannot be resolved through negotiations, the issue may be taken to court proceedings. Such proceedings may take up to a year or more. The employee normally remains employed during the entire proceedings and is entitled to all his/her employment benefits during the notice period.

If a termination is challenged solely as being made contrary to the priority rules described above, the employee cannot claim that the termination shall be declared invalid and will not remain employed during any court proceedings.

The remedies available in case an employee challenges a summary dismissal are the same as described above. However, in this situation, the employee will normally not remain employed during any court proceedings.

The act contains rather general provisions regarding the work environment. It focuses on the physical as well as the psychological and social aspects of the work environment. A fundamental principle is that work should be adapted to the physical and psychological situation of the employee. In addition, the act contains rules limiting the possibilities for employers to employ minors. The Swedish Work Environment Authority is authorised by the act to issue more detailed regulations regarding the working environment. The authority has issued a large number of ordinances based on this authorisation. The ordinances cover all aspects of the work environment and are the main instrument for implementing EU-legislation regarding work environment.

One important part of the Act is its provisions regarding cooperation between the employer and the employees and their union representatives, in order to maintain and improve the work environment. According to these rules, the employees and their trade unions may appoint one or more safety representatives at the workplace. Furthermore, workplaces with more than 50 employees shall have a safety committee, which shall consist of representatives of both the employer and the employees. The act contains rules which, in some critical situations, entitle a safety representative to stop a specific work from being performed. This may be the case if the work would entail an immediate and serious danger to an employee’s health or life.

The Systematic Working Environment Management

According to the Work Environment Act, every employer shall systematically plan, manage and control its business so that the work environment is satisfactory and fulfils the requirements of the Work Environment Act and the ordinances of the Work Environment Authority. Furthermore, the employer shall investigate all occupational injuries, continuously investigate the risks that come with the business and take the actions that the risks necessitate. The employer must also make a plan for eliminating all risks that cannot be remedied immediately. In addition to this, the employer must make sure that there is a suitable organisation for rehabilitation and adaptation of the work for sick employees. The above obligations are referred to as the employer’s “Systematic Working Environment Management”.

The main obligations in the Systematic Work Environment Management are the following:

- Create a Work Environment Policy.

- Create routines for how the working environment management shall be carried out.

- Distribute the various tasks in the Systematic Work Environment Management, to ensure that everyone who is involved in the work is aware of his/her responsibilities.

- Make sure that employees have good knowledge of their work and are well informed about risks at work. Make written instructions when risks are serious.

- Continuously monitor the work environment in the workplace.

- Make risk assessments, to identify the risks for ill health and injuries that exist at the workplace, including an assessment of the seriousness of the risks. Make new risk assessments when circumstances in the work environment are changing.

- Immediately remedy deficiencies in the work environment.

- Create an action plan for such deficiencies in the work environment that cannot be remedied immediately.

- Investigate the causes of any occupational injuries and any near-accidents.

- Follow-up on the Systematic Working Environment Management at least once per year.

Delegation of Responsibilities for the Work Environment

The main responsibility within a company for creating a good work environment lies with the board of directors and the general manager. They may in case of negligence in relation to obligations under the Work Environment Act, be convicted of health and safety offenses and sentenced to fines. Normally, that happens when it comes to fatalities or accidents with serious bodily injury. The company can also be assessed a corporate fine, which normally is the only sanction in case of less severe accidents.

In most companies it is not possible for the board of directors and general manager to be directly involved in the management of the work environment. It is therefore often necessary to distribute the tasks for the work environment to others within the company, in order for the company to be able to fulfil its obligations regarding the work environment. It is important to stress that the distribution of tasks does not imply that the responsibilities under criminal law is delegated.

Thus, the company cannot decide which if its officials that shall be exposed to the risk of being punished under criminal law in case of a grave breach of the work environment rules. However, if the company has made a correct delegation, the responsibility under criminal law will probably fall on the person who has in fact been responsible for the work environment in the area where a breach of the work environment rules has occurred and. To be punished person must have proven negligence. Should a delegation be tried by a court, the following five criteria must be fulfilled in order for a correct delegation to be at hand:

- There must be a clear need for the delegation

- The person who receives the delegation must be in an independent position.

- The person who receives the delegation must be sufficiently competent for the delegated task.

- The person who receives the delegation must have the proper authorisation to take any necessary decisions.

- The responsibility for different tasks must be clear. Thus, it is important that the delegation has been evidenced in writing.

More information

Industriarbetsgivarna produce publications and reports within the work environment area. Please find our publications, of which some are translated into English via link below.

The Discrimination Act (2008:567)

The Swedish Discrimination Act is based on directives from the European Union and establishes a general framework for combating discrimination together with promoting equal treatment in the working life.

Prohibition of discrimination

The Discrimination Act prohibits discrimination on the grounds of sex, transgender identity or expression, ethnicity, religion or other belief, disability, sexual orientation and age. An employer may not discriminate against an individual in the capacity as an employee, temporary employee, a job-seeker, a trainee or a school pupil in a work experience position. Discrimination is prohibited in any situation within the working life, but could for an example arise in a situation of recruitment, dismissal, promotion, training, supervision, applying terms and conditions of employment, day to day management and so on.

Both direct and indirect discrimination is prohibited. Direct discrimination is established to be when someone is disadvantaged by being treated less favorably than someone else is being treated, has been treated or would have been treated in a comparable situation, and this disadvantage is associated with one of the grounds of discrimination. Indirect discrimination is stated to be when someone is disadvantaged by the application of a provision, a criterion or a procedure that appears neutral, although it may put individuals of a certain ground of discrimination at a disadvantage, unless the provision, criterion or procedure has a legitimate purpose and means which are appropriate and necessary to achieve this purpose.

In addition, the act prohibits harassments, sexual harassment and giving instructions to discriminate. It also prohibit employers from subjecting employees who have reported discriminations or participated in investigations of discrimination to reprisals.

Contravening the prohibition against discrimination results in a liability to pay damages, both for the offence itself and for economic loss. Furthermore, an agreement is invalid to the extent that its provisions are discriminatory.

Active measures against discrimination

The Act also includes an obligation for the employer to investigate any situation where the employer receives knowledge that an employee deems himself/herself to have been subjected to discrimination. If the conclusion of such an investigation is that an employee has been discriminated, the employer shall take any reasonable action to prevent discrimination from occurring in the future.

It shall also be mentioned that if a job applicant has not been employed or selected for an employment interview, or if an employee has not been promoted or selected for education/training or for promotion, the applicant shall, upon request, receive written information from the employer about the education, professional experience and other qualifications that the person had who was selected for the employment interview or who obtained the job or the place in education/training.

An employer should also work actively to bring about equal rights and opportunities in the working life regardless of the grounds of discrimination. The regulation concerning the general obligation of employers to promote equality includes an obligation to every three years survey and analyze if there are any unreasonable differences between the salaries of men and women. If the employer has more than 25 employees the obligation also includes to draw up an action plan for gender equality, which includes a plan for equal pay between men and women. These rules are not sanctioned by damages. However, the Equality Ombudsman has the authority to ensure compliance in this area and may order an employer to carry out certain actions or risk being fined by the Board against Discrimination.

Other legislation

In the context of discrimination, it is also worth mentioning that there are two other Acts of interest. First of all, the Parental Leave Act stipulates a prohibition against disadvantaging employees on parental leave, which can be seen as a regulation within discrimination. Second, there is the Act Against Discrimination of Employees Working Part-time or on Fixed-term Agreements. This act prohibits both direct and indirect discrimination of part-time and fixed-term employees. Again, an agreement is invalid to the extent that its provisions are discriminatory. In addition, an employee who has been the victim of discrimination is entitled to receive damages, both for the offence itself and for any economic loss that the discrimination has caused.

The Act on the Position of Trade Union Representatives at the Workplace regulates only the position of trade union representatives. The law applies to employees who have been appointed by the local union organisations bound by collective bargaining agreements to represent the employees at their workplace in union activities which affect their relations with the employer. It should in this context be noted that the concept of union activities is extremely wide-ranging. The local union branch is in principle free to decide how many representatives are to be appointed at a workplace.

Union representatives may not be prevented from performing their union work and may not be given less beneficial terms and conditions of employment on account of their union activities. Needless to say, the representatives may not be discriminated against.

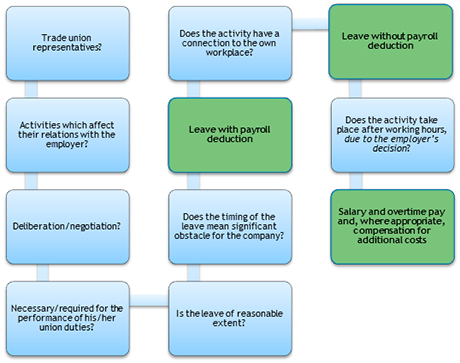

A union representative is entitled to such leave as is necessary for the performance of his/her union duties. This leave may not, however, be more extensive than is reasonable in view of the conditions of the workplace and may not be taken at a time which may seriously impede the performance of normal work. How much leave and when leave may be taken shall be decided after discussions with the employer. A union representative is entitled to unchanged salary and other benefits during leave for union activities relating to his/her own workplace.

The union normally has an interpretive precedence in case of a dispute between the employer and the union concerning the application or interpretation of the act, i.e. the union’s view shall prevail until the dispute has been resolved.

The Board Representation (Private Sector Employees) Act

The employees in a limited liability company, economic association and certain other types of companies with at least 25 employees are entitled to appoint two members and two deputy members to the board of directors of the company. Furthermore, in companies with at least 1,000 employees and which are engaged in several different industries, the employees may appoint three board members and three deputy board members. However, a prerequisite for the right to appoint board members and deputies is that the company is bound by at least one collective bargaining agreement.

The employee representatives should preferably be appointed from amongst the employees at the company or, for parent companies, from amongst the employees of the group.

The employee representatives have the same rights and obligations as the other board members. Furthermore, the employee deputy board members have an increased right to participate at the board meetings, as compared to the deputy board members appointed by the general meeting of the company. The employee representatives may not participate in dealing with issues that relate to the collective bargaining agreement, industrial actions or other issues where a union organisation at the workplace has a material interest that may conflict with the interests of the company.

European Works Councils

Since 1996 Sweden has had a European Works Council Act based on the European Council Directive 94145/EC on the establishment of a European works council or a procedure in community-scale undertakings and groups of undertakings for the purpose of informing and consulting employees.

Community undertakings covered by the Act must have at least 1000 employees in EEA countries and at least 150 employees in each of at least two EEA countries. The Act, contains complicated rules for the establishing of a works council or some other model for employee influence.

Collective Agreements in English

Most of the collective agreements within Stål- och metallindustrin (Steel and Metal Industry), SVEMEK (Welding Engineering Industry), Byggnadsämnesindustrin (Construction Materials Industry), Sågverksindustrin (Sawmill Industry), Massa- och pappersindustrin (Pulp and Paper Industry), and Gruvindustrin (Mining Industry) have been translated into English.

Prevailing language: These are only translations of the Swedish agreements.

Links to the agreements can be found below. Please note that the agreements are only available to Industriarbetsgivarna’s members and that you need a log-in to our website Industriarbetsgivarguiden to be able to view them.

Steel and Metal Industry

Welding Engineering Industry

Construction Materials Industry

Sawmill Industry

Pulp and Paper Industry

Mining Industry

Membership

Industriarbetsgivarna is one of almost 50 members of the Confederation of Swedish Enterprise (Svenskt Näringsliv), hence members of Industriarbetsgivarna are also members of Svenskt Näringsliv.

The Collective Agreements

Collective agreements ensure that both employees and employers know what applies at the workplace, such as pay and general conditions, so that you can concentrate on the core business.

As a member of Industriarbetsgivarna you are bound to follow the provisions of the collective agreements that apply to your business. This includes an obligation to take out certain collectively agreed pensions and insurances for your employees.

For guidance regarding pensions and insurances please use the service from Avtalat.

Industriarbetsgivarguiden

Industriarbetsgivarguiden is a privilege for you as a member. That is where we collect all our information for you in one place including the collective agreements, and various agreements between employers and employees.

Apply for Membership

To submit for membership in Industriarbetsgivarna and Svenskt Näringsliv fill in one of the forms below (on line or PDF). If you choose the PDF version send it to info@industriarbetsgivarna.se.

Should you have any questions do not hesitate to contact us.

Application in English

(Signed with SMS or touch screen)

Membership Application Form

(Signed with a pen)

Advisory service (members only)

Contact:

Telephone: +46 8 762 67 70

E-mail: rad@industriarbetsgivarna.se

Please consider the EU’s general data protection regulation, GDPR. Click to learn more.

Opening hours:

Monday-Thursday 08.30-16.30.

Friday 08.30-16.00.

Opening hours during June, July and August:

Monday-Friday 08.30-16.00.

July 14th – August 1st 2025:

Only e-mailing after lunch.

Closed for lunch between 12.00 and 13.00.